Meret Oppenheim

Here lives the Witch

05.09.2020 – 31.10.2020

OPENING: 5 September 2020, 10 – 4 pm

Exhibition catalogue with a text by Dr. Simon Baur available on request.

-------------------------

Grabbing Hope by the Horns

Meret Oppenheim’s Great Shadow Times Table

“Dreams are important to the way I lead my life,” explained Meret Oppenheim in an exchange of letters with VALIE EXPORT in 1975. “A dream can confirm an attitude or direction, or make me change it. I don’t use dreams for my ‘work.’ (That would be copying!) If I capture three or four dreams in an image, I consider it a document.” (1)

Much of what Oppenheim would later transform into art had its origins in her childhood and youth. Her grandmother, Lisa Wenger, was an artist and author who took painting lessons with Hans Sandreuter in Basel and later studied art in Paris, Florence, and at the Düsseldorf academy. She wrote numerous children’s books—the most famous of them, Joggeli söll ga Birli schüttle, first appeared in 1908 and is still in print even today—and illustrated them in her own distinctive brand of Jugendstil with folkloric elements worked into it. Her illustrations often recall that pioneer of artist books for children, Ernst Kreidolf, but are deliberately more childlike in design, her audience being overwhelmingly made up of young readers.

Influences and Ideas

Lisa Wenger perhaps knew Kreidolf, since they both belonged to the same generation, and Meret Oppenheim, too, quite likely grew up with his picture books and would have known the anthropomorphic flowers, plants, and bushes, the grasshoppers, caterpillars, butterflies, and beetles that populate them. Her works certainly echo some of the latent melancholy of his children’s books. Take Kreidolf’s Flower Fairy Tales, for example, in which Mr. Primrose and Mrs. Gentian take a stroll together through a forest full of flowers, followed by Margaret the nursemaid with the children. Ostensibly an idyllic scene, it acquires its melancholy subtext from the poem accompanying it, which anticipates how it will all end:

The happy couple love to stroll,

and promenade often every day,

till autumn comes and takes its toll,

And all the flowers wilt away—

Mr. Primrose, too, with his dear wife,

good Mrs. Gentian at his side. (2)

This is also the book that contains the picture of butterflies and moths having a party in a pavilion, while a thunderstorm rages outside—an image that Oppenheim must have had in mind when she invented her water pavilion Under the Pond or “gazebo made of water,” as she herself called it. It is certainly a delightful idea: a cylinder-like structure containing a kitchen and café counter and around it people drinking warm drinks and eating cake, safe inside the water curtain encircling them.

There can be no doubt that Oppenheim frequently drew inspiration from works of literature. The two drawings of 1931 called Suicide‘s Institute might well be connected with the book of that name, Un istituto per suicidi by Basel author Gilbert Clavel. Clavel was certainly an inspiring figure. After studying art history and Egyptology, he lived mainly on Capri, and in 1918 co-directed with Fortunato Depero a production of the Balli plastici, a fairy-tale drama in five acts with music by Alfredo Casella, Gerald Tyrwhitt, Béla Bartók, and Francesco Malipiero, at the Teatro dei Piccoli in Rome. He spent his remaining years remodeling Positano’s sixteenth-century “Saracen Tower,” which had formerly served to defend the town from attacks from the sea, and transforming it into an enigmatic Gesamtkunstwerk. Another possible source of ideas for Oppenheim’s early drawings is Steppenwolf, by Hermann Hesse, who from 1924 to 1927 took lodgings with her aunt, Ruth Wenger. Many of the titles she gave her works—The Erl Queen, Little Red Riding Hood and Wolf, and Genevieve‘s Mirror, for example—reference fairy tales, poems, or at any rate tales from her childhood and youth.

Experiences in Paris

Meret Oppenheim and her friend Irène Zurkinden went to live in Paris in the spring of 1932. On arriving in Paris—having first drunk themselves into a Pernod stupor on the train—they went straight to the Café du Dôme, which in those days was a favorite haunt of artists. They also attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière from time to time, but generally preferred to work at home and in cafés. It was in Paris that Oppenheim wrote her first poems, like this one:

For you—against you

Cast all stones behind you

And let the walls go.

At you—on you

For a hundred singers over you

The hooves tear away.

I disembowel my mushrooms.

I am the first guest here in the house.

And let the walls go. (3)

There are echoes here of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem “Autumn Day.” Presumably Oppenheim’s artist friends in Basel had told her of the time in 1920 when Rilke had read some of his poems at the studio of the artist Niklaus Stoecklin, an exponent of Neue Sachlichkeit. Did she also know that immediately after the reading, Stoecklin’s sister Francesca had held a séance that was also attended by Rilke himself? That was the kind of thing that Oppenheim’s grandmother Lisa Wenger did, too. We know from Theo Wenger's biography of his wife that she did indeed engage in “table turning”: “The soothsaying medium was the ‘Tischli,’ a little round table with twenty-four letters of the alphabet [sic] around the circumference. Seated around it were several people (Lisa Wenger had to be among them or at least in the same room) and in the middle of the table was an upturned water glass. Everyone placed a finger on the glass, which as soon as one of those present had asked a question (whether out loud or only to him or herself), began to move toward the letters, zigzagging along from one letter to the next and so forming words which, combined into sentences, invariably yielded an answer that made sense. Rhymes were not uncommon either.” (4) Some of Meret’s later poems might well have been “written” at the “Tischli.”

Contact to the Surrealists

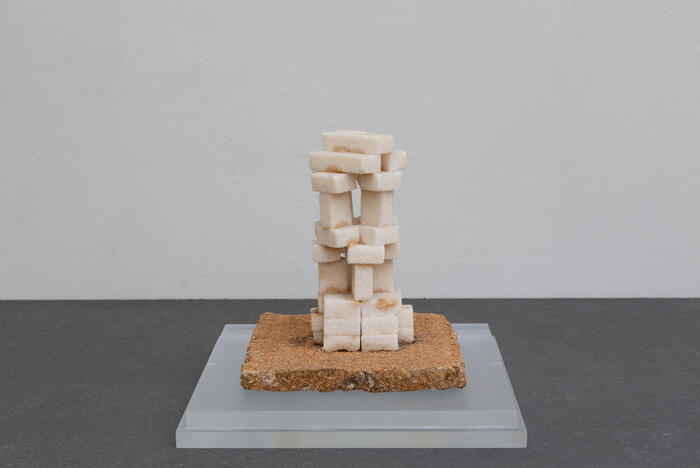

In Paris Meret Oppenheim visited Alberto Giacometti and socialized with two other artists from Basel, Hans Rudolf Schiess and Kurt Seligmann. Through them she became acquainted with Hans Arp, Sophie Taeuber, and Max Ernst, with whom she had a passionate, year-long amour fou, but then rejected on the grounds that he was standing in the way of her own development. Her relationship with Marcel Duchamp, which lasted until he went into exile in New York in 1942, must have been more fulfilling. Not only did he motivate her to work hard on making objects, but he also tried to find her a job as a conservator. She, for her part, found Swiss art collectors interested in buying some of his paintings and objects and tried to bring about an exhibition of his works at the Maison Schulthess in Basel, which hosted her own first solo show in 1936. Arp and Giacometti were probably the ones who visited her in her studio in the late summer of 1933 and invited her to exhibit her works alongside the Surrealists at the Salon des Surindépendants. It was there that she met Man Ray, who was also among the exhibitors and who engaged her as a model soon afterward. The famous nude photos of her next to a printing press, one of which was published in the magazine Minotaure, were taken in the studio of Louis Marcoussis. While Oppenheim was active in André Breton’s circle and attentively followed the Surrealists’ debates, she still spent the summer months in Ticino, where her grandmother Lisa Wenger welcomed guests from all over the world. These are the two geographical poles between which her works can be located: Carona, which stood for the world of her grandmother and her childhood, and Paris, a cosmopolitan city and hotbed of Surrealist debate. The former of these, the village in Ticino, not only laid the groundwork for Oppenheim’s Surrealism, but it also gave her a place to which she could retreat to work on her art undisturbed. It was in Carona that she produced her first objects, such as a rounded wooden board with slits cut into it, into which she stuck white sugar-coated almonds. The Head of a Drowned Man, third state, she later gave to Yves Tanguy. The form would be a recurrent one in those works of hers that have to do with faces and with water in a narrower—or a wider—context.

Oppenheim’s father, a physician in Steinen im Wiesental in Germany, was worried about his daughter and sent her to Carl Gustav Jung, who reported back to him in September 1935 as follows: “I don’t believe the case is all that bad. She seems to have learned a thing or two from her collision with the world and there is no reason why this knowledge should not deepen considerably in the course of time. It is certainly not my impression that there are any neurotic complications. Her artistic temperament on the one hand and the youthful disorientation of an age that has to measure itself against the rationality of the nineteenth century are surely explanation enough for the unconventionality of her stance. I also have the impression that, given your daughter’s natural intelligence, the struggle with reality will, in a few years’ time, yield a seriousness that may give us hope of her becoming well adjusted to the realities that hold sway.” (5) Oppenheim recorded her own response to the meeting with Jung not long afterward: “I found the afternoon spent with him very pleasant. He said, among much else: All women are expected to be angels. (very important!)” (6) The same idea, albeit worded rather differently, came up in her acceptance speech on receiving the Art Award of the City of Basel forty years later: “A great work of literature, art, music, philosophy is always the product of a whole person. And every person is both male and female. In ancient Greece, men were inspired by the Muses, which means that the female tendency within them shared in their creations, and this still applies today. Conversely, the male tendency is contained in the works of women.” (7)

Solo Exhibition in Basel

Meret Oppenheim’s first solo show was held at Marguerite Schulthess’s gallery in Basel in 1936. Max Ernst composed a text for the invitations in which it was announced that the artist would be showing “painted, drawn, glued pictures” and objects, such as Ma gouvernante—My nurse—Mein Kindermädchen, a pair of glued-together high-heeled shoes now in the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. The critic reviewing the show for the National-Zeitung was unimpressed: “Too little substance, too little ‘objet,’ the word Meret uses for her products, too little ability, and above all too little understanding of the real problems of an ars nova. Granted, Meret does not imitate, since she lacks the skill and technical savoir faire for that, and the will to ‘transgress.’ There is altogether too little will; more a deliberateness and a succumbing to inchoate dreams of the phantoms of modern sexual psychology.” (8) The critic for the Basler Nachrichten—probably Hans Graber, who was a great champion of modern art—was not only more positive, but also prophetic: “Here Meret Oppenheim shows what she can do and that she is talented. In which direction her particular gift will take her cannot yet be foreseen, as she is venturing down the most diverse paths, trying things out, playfully experimenting, and not yet leaving a clear trail. Will she paint, glue, work in three dimensions? Will she continue to unburden herself of a dream by painting a ghost on snakeskin, by reminting the fantasy as something more akin to an accusation: Quick, Quick, The Most Beautiful Vowel is Voiding, or by gluing drinking straws onto a black, and trouser buttons onto a white, ground?” (9) She is unlikely to have sold anything at that first exhibition and some of the works she later destroyed. Others, however, she patched up or remade.

Breakfast in Fur

In 1936 Oppenheim’s father had to leave Steinen im Wiesental where he had been practicing as a physician, and as that rendered him unable to continue supporting his daughter financially, she decided to try her hand at commercial jewelry and fashion design. But her designs were too extravagant even for the most progressive couturiers, although Elsa Schiaparelli did commission some bracelets made of sections of polished copper piping covered in fur.

It was Pablo Picasso who gave her an input out of which her fur-covered teacup would emerge, and André Breton who invented the title, Déjeuner en fourrure, which was itself a paraphrase of Édouard Manet’s famous Déjeuner sur l’herbe. That the success of the fur teacup at such an early stage in her career sparked a crisis is hardly surprising. Oppenheim reflected on this in a letter to her sister Kristin of May 1981: “But probably it was the tremendous success of the fur teacup (in the Mus. of Mod. Art, New York, 1936) that precipitated the breakdown, the turning point where I had to tell myself, or ask myself, ‘So am I really an artist?’—and where the crisis set in. And when in 1954 it finally dawned on me and it was all over (in October), I discovered that, in my innermost self, I, too, had consistently doubted women’s ability to accomplish anything! How right Jung was when he said: ‘Whoever has feelings of inferiority is inferior. But with this feeling the unconscious spurs us on to do better, to keep going.’ (That’s not a quotation. I’m just repeating the gist of it.” (10)

But she did learn some lessons from the teacup. As Max Ernst had prophesied in the text he wrote for the invitation to her show at the Galerie Schulthess, she “politely locked herself up in an air vent and swallowed the key. Then, after fasting for forty days, she suddenly burst forth and since then has played happily—I wonder why?—with the headlands of coastal landscapes and foothills.” (11) Describing her artistic technique, Ernst had previously remarked: “Her palette is full of the remains of plants and animals. That is why her pictures keep best inside lead boxes and stone bridges.” (12) Her work did indeed change drastically during those years of crisis. At first only tentatively, but then more and more resolutely, as she managed to “cast all stones behind her.” “This ‘new style,’ since 1939, for a long while did not feel right to me, even though I had just had a major triumph with it,” she wrote in her album From Childhood to 1943. “The last picture that can be counted among this ‘imageri’ is the unfinished ‘Apoll u. Daphnë’ [...].” (13)

Categories?

The discontinuity of Meret Oppenheim’s oeuvre has been remarked on by various commentators. Yet her work can still be categorized. One good starting point, apart from the obvious one of Surrealism, is the theory of the four elements, for it was not by chance that on her fiftieth birthday she produced four colored-crayon drawings titled The Four Elements—Fire, Air, Earth, Water. Among her many works to allude to the symbolic and metaphorical meanings of water, alongside the fountain models, are Head of a Drowned Man, Under the Raincloud, which incidentally was used as the motif for a Swiss postage stamp, View from the Gazebo, Octopus’s Garden, and Lagoons. Then there are all the clouds, stars, roots, trees, birds and insects in her work, to say nothing of all the witches, ghosts, fairies, fantasy figures, and, of course, the memories with which it is teeming. Even the memory of the fur teacup, which for her personally brought about a metamorphosis comparable with that experienced by Gregor Samsa in Franz Kafka’s eponymous novella, keeps on cropping up. Yet only rarely are the four elements unambiguous. And often there are formal similarities, despite the divergent themes; hence the assumption that we are dealing with a larger context here. Take the drawing The Hand of Melancholy of 1943, for example, which certainly bears an affinity to the drawing Swallows of the following year. What makes this example so interesting is that it depicts melancholy, commonly thought of as the mother of all art, rousing herself from her torpor and transforming herself into a swallow in flight—the image of freedom and independence par excellence. After all, freedom is not just the “freedom of those who think differently,” as Rosa Luxemburg put it, but it is also something that according to Oppenheim “is not given to you, you have to seize it.” And seize it she did. Thus she remains the mysterious shaman, an artist who communed with elemental spirits and who left us with mysteries that to this day have remained unsolved. How right Max Ernst was when, on that famous invitation of 1936, he wrote: “Who has outgrown us all? Meretlein! The better Da- (to be continued).” (14)

Simon Baur

1 VALIE EXPORT in conversation with Meret Oppenheim, in Magna. Feminismus. Kunst und Kreativität. Ein Überblick über die weibliche Sensibilität, Imagination, Projektion und Problematik, suggeriert durch ein Tableau von Bildern, Objekten, Fotos, Vorträgen, Diskussionen, Lesungen, Filmen, Videobändern und Aktionen, edited by VALIE EXPORT, exh. cat. Galerie nächst St. Stephan, Vienna 1975, pp. 4‒6. Here quoted from Meret Oppenheim. Retrospective—an enormously tiny bit of a lot, edited by Therese Bhattacharya-Settler and Matthias Frehner, Ostfildern 2006, p. 137.

2 “Machen ihre Promenade / Täglich oftmals auf und ab, / Bis im Herbst, es ist zu schade, / Blatt und Blume sinkt ins Grab – / Auch Herr Schlüsselblum und Frau / Enziane Himmelblau,” from Ernst Kreidolf, Blumen-Märchen, Bern 1963, n.p.

3 Meret Oppenheim, Husch, husch, der schönste Vokal entleert sich. Gedichte, Zeichnungen, edited by Christiane Meyer-Thoss, Frankfurt am Main 1984, p. 31. Here quoted from Meret Oppenheim Retrospective, edited by Heike Eipeldauer, Ingried Brugger, and Gereon Sievernich, Ostfildern 2013, p. 148 (trans. Catherine Schelbert).

4 Theo Wenger, Biografie, unpublished typescript, p. 11.

5 Meret Oppenheim, Worte nicht in giftige Buchstaben einwickeln. Das autobiografische Album “Von der Kindheit bis 1943” und unveröffentlichte Briefwechsel, edited by Lisa Wenger and Martina Corgnati, 2nd ed., Zurich 2015, p. 51.

6 Ibid.

7 Bice Curiger, Meret Oppenheim. Spuren durchstandener Freiheit, Zurich 1989, p. 130, available in English as Bice Curiger, Meret Oppenheim: Defiance in the Face of Freedom, with texts and poems by Meret Oppenheim et al., Zurich and Cambridge Mass. 1989. Here quoted from Meret Oppenheim Retrospective 2013, (see note 3), p. 270.

8 “Basler Kunstsalons. ‘Objets’ von Meret Oppenheim in der Galerie Schulthess,” in National-Zeitung, No. 197, 29 April 1936.

9 “Ausstellung Maison Schulthess,” in Basler Nachrichten, No. 113, 25/26 April 1936.

10 Oppenheim 2015 (see note 5), p. 17.

11 Quoted after Curiger 1989 (see note 7), p. 29.

12 Ibid.

13 Oppenheim 2015 (see note 5), p. 189.

14 Quoted after Curiger 1989 (see note 7), p. 29.

Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim